Building empathy through remote user research

User research isn’t just good ethics. It's also the only way your product or service is going to succeed. You can’t make effective digital tools without speaking to the people who are going to use them, but how do you begin to approach remote user research?

Almost two thirds of charities are more stretched than ever, with an increase in demand for their support, at the very time when they can’t offer them in their traditional face to face settings. Now, more than ever, digital tools that help support those in need are essential. But, we won’t build the right tools if we don’t also build a deep level of empathy with those using them.

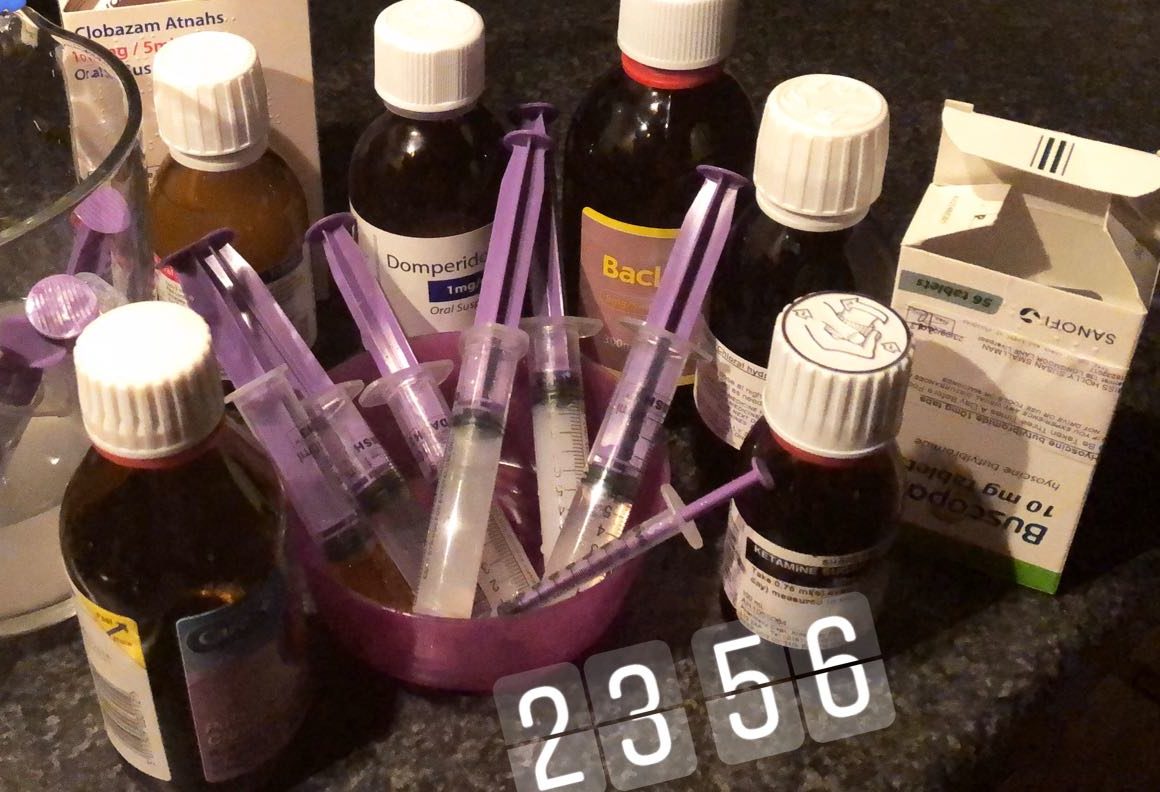

Pre-2020, building empathy through user research might have looked a little bit like this: Sitting in a room with pharmacists and nurses to understand their experiences working with parents of seriously ill children:

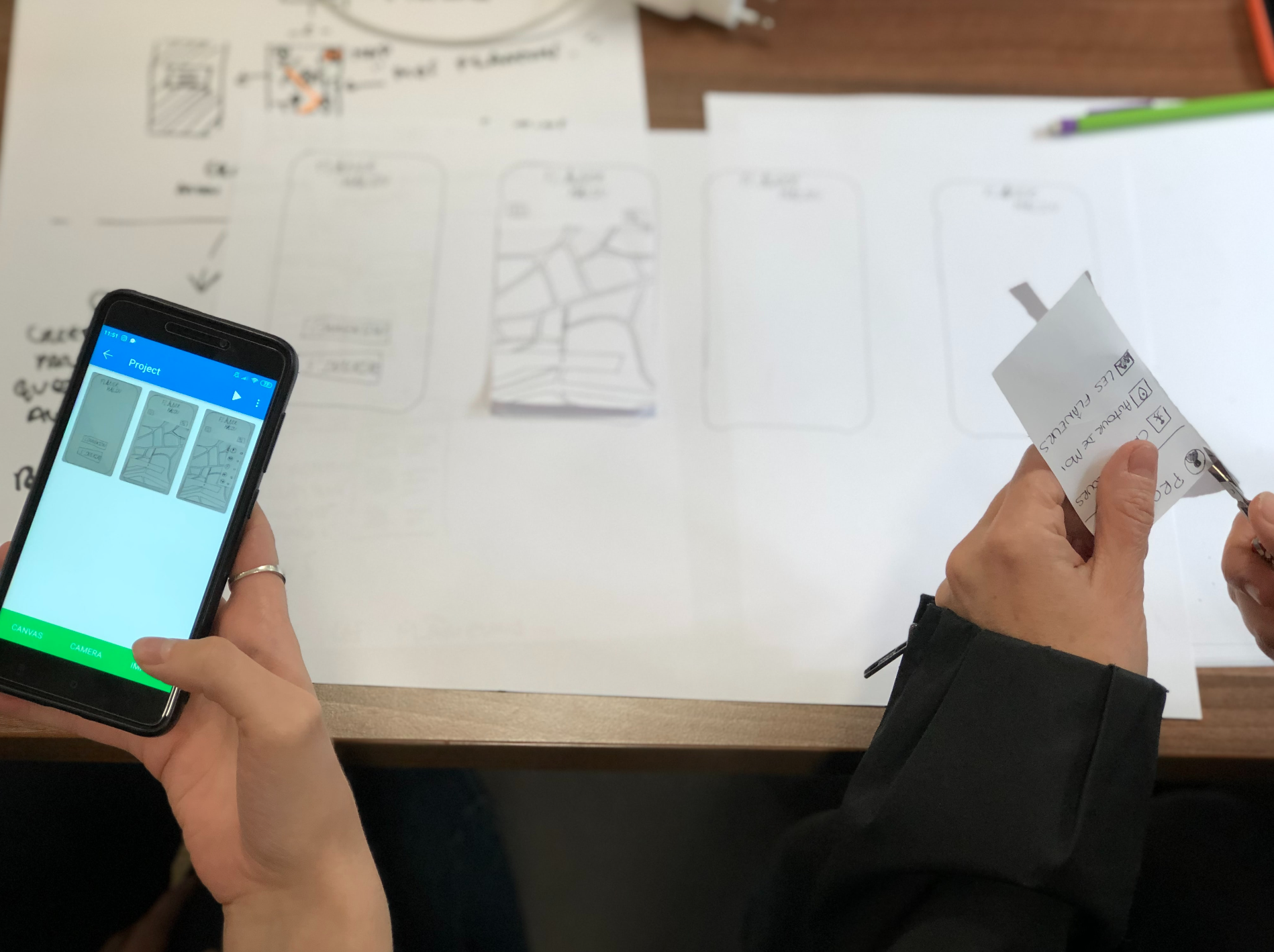

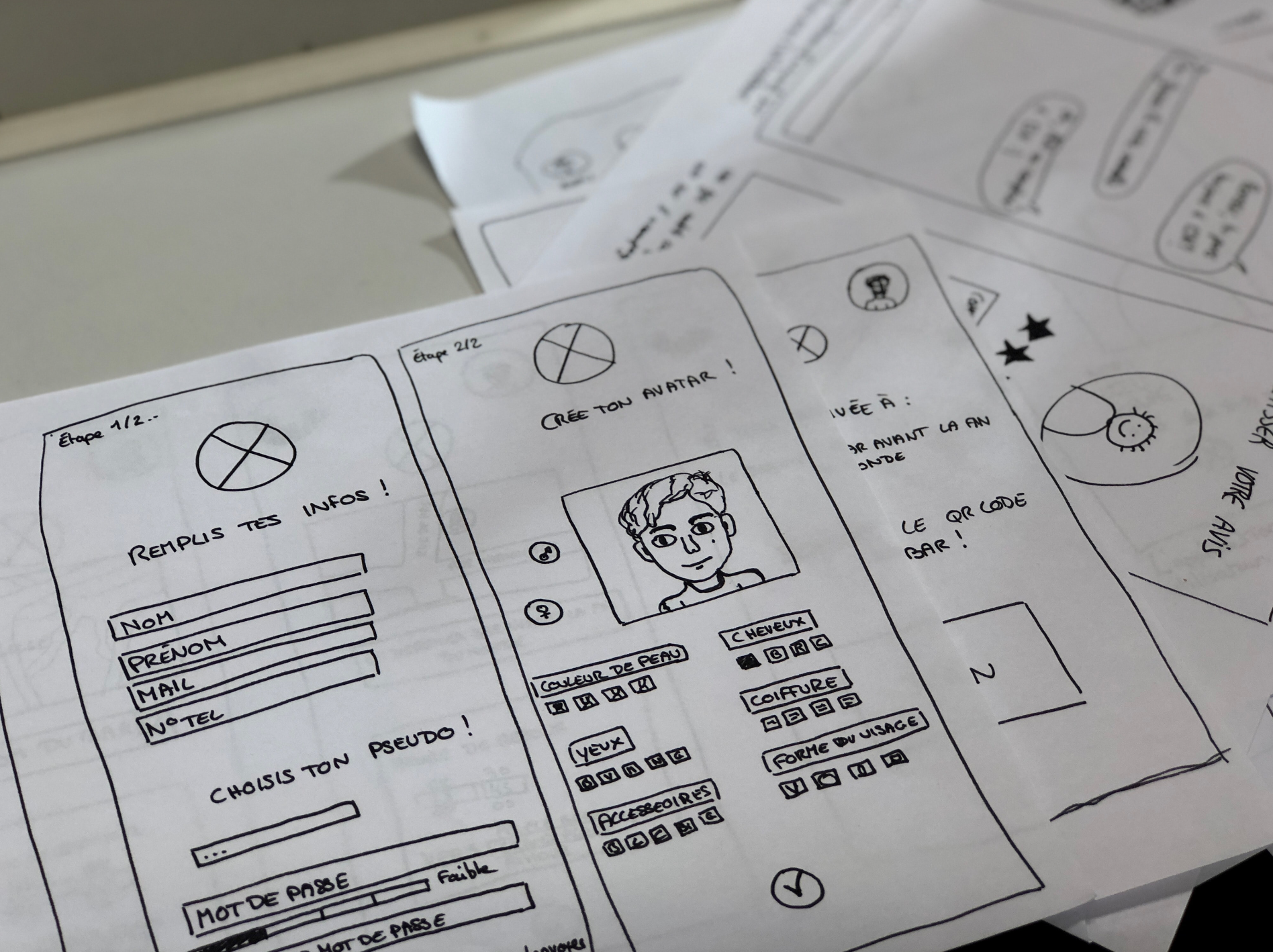

And pre-2020, usability testing might have looked something like this; going out into the field and putting our creation in the hands of people who will use it:

Lately there’s been no possibility of gathering in a room, but user research must keep happening. Even if we think we know our user base inside out, Covid presented the world with a number of new challenges, and people’s wants and needs may have changed.

Our team has experience building user empathy through a screen – even pre-pandemic we built digital solutions to human problems from opposite ends of the country before WFH was mandatory.

But some charities are diving head first into remote user research with little or no experience, and it’s scary! Change can be challenging, and whilst It’s easy to assume the worst when moving from familiar approaches and tools to new ways of working, we’ve seen firsthand that there is always more to learn.

Truth be told, we were concerned about the loss of useful insight that we’re used to gaining from body language. We thought we might not have conversations that were as natural as in person. And we expected an increased cognitive load for both our research participants and for ourselves. While some of this was accurate, there are also a lot of unexpected benefits you just don’t get when face-to-face:

- By removing the hurdle of distance and travel, you increase efficiency.

- Sudden access to a geographically diverse group makes for a more representative sample.

- You can test your product on all kinds of devices, instead of handing all participants the same laptop or tablet.

- You witness a more real experience. Whilst phone notifications or needy pets may feel detrimental to concentration and focus, this is actually more reflective of real life.

Remotely, people are often that little bit braver. Things happen virtually that would never happen face to face. The Handforth Parish council would never have sat round a table and yelled at each other (we hope!), and Jackie Weaver would never have physically kicked someone out of the room. This may seem scary but it’s actually valuable; it can lead to more earnest feedback for your tool.

The reality is, at Reason we’ve been using remote research methods long before there was a pandemic. And yet, a fully-remote year has just helped us realise how often remote research is the best approach, pandemic or no pandemic.

Here’s our seven tips for your next remote research venture.

1. Focus on accessibility from the word go

Firstly, we must spotlight accessibility – something that should always be top of mind for any user research venture, whether remote or face-to-face.

Last year, our research found that online charity services are 7% more likely to be inaccessible than offline services. With many places still closed, it’s crucial that we are all taking steps to make sure online charity services are accessible to everyone.

In an ideal world, the best way to make accessible sites is by doing qualitative research upfront and including people with access needs. We’d also strongly recommend continuing this research at each stage of the project.

Accessibility isn’t only important in disability-focused projects. For example, every website nowadays should be optimised for screen readers, so you should be speaking to people with visual impairments from the get go.

Factoring in accessibility to your user research isn’t just about checklists and token processes, you need to include real experiences from the very beginning. That way, when you’re building your product, that deep, instinctive understanding of different people’s accessibility needs will always be present and considered.

2. Include asynchronous research

Similar to the theme of accessibility, you should always make life as easy and convenient as possible for the people you’re researching. This is especially important for charities, who could potentially be speaking to vulnerable populations, people who struggle to travel, or those with complex daily routines.

We had to think outside the box and implement unique techniques for this very reason during our project with WellChild, the national charity that supports parents and carers of seriously ill children.

Being a parent or carer in this scenario is a relentless 24 hour responsibility, involving cumbersome routines and very little support. We ran a design sprint with WellChild to develop a medicine management solution which would genuinely meet parents’ needs. So, we needed to understand what these parents’ lives looked like. But due to their demanding care routines, only a few parents could join us in-person.

In an aim to gather as much authentic insight into their lives as possible and to increase the pool of people we could reach, we adopted a remote, asynchronous approach to user research.

We asked parents to complete ‘WhatsApp diaries’. These diaries provided our team with a snapshot of what a week in their shoes looked like. They shared messages, photographs, and videos that detailed their intimate realities. From these diaries, we could piece together insights from a diverse set of experiences.

The data we got from these diaries changed the scope of the medicine management tool we built, and the reality truly hit home for stakeholders, who were blown away by the impact it would have on parents’ and carers’ lives.

Asynchronous research methods like diary studies can be completed by time-poor participants at a time that suits them. These methods also avoid putting any potential added pressure or stress onto research participants – something we strive to avoid wherever possible.

In fact, why not push for the other end of the scale: supporting participants to actually enjoy and feel engaged in the research. The more creative you are in the stimulus you give people to complete, the more interesting and liberating it can be to participate in.

Alternatively, you can take a hybrid asynchronous/synchronous approach. With this, you can minimise face to face time by having participants pre-complete a diary, and then using that as stimulus for an efficient discussion.

3. Try ditching video

We’ve all fallen into the trap of assuming that a video call is the way to meet virtually. In actual fact, we’ve often achieved better results when researching and testing by holding audio-only sessions. After all, video calls with a stranger can be intimidating!

It may feel counter-intuitive, but try turning off video. It’s not just good for your wi-fi, it could also increase the empathy you gain from each session with your participants.

This notion is even supported by research. In one 2017 study on digital empathetic accuracy, video was taken away during test conversations. This meant that people focused more on what they could hear rather than being distracted by all the visual information on a video call. The result was participants in the conversation more accurately predicting what the other person had been feeling or thinking.

Setting up research on the phone has practical benefits too: it’s the best approach for some audience groups, it reaches a wider geographic sample, it’s easy to arrange timings, but it also results in high quality research insights.

4. Ditch fancy tech altogether

Recently we started an exciting partnership with Blind Veterans UK, the charity that supports vision-impaired ex-Service men and women. We spoke to some of their beneficiaries over the phone, uncovering some amazing and genuinely insightful information.

Through a simple conversation over a landline, we really got under the skin of what the constraints were in terms of what we could build for the project. Our findings forced us to rethink our initial grand ideas around tech and focus on what was going to improve these veterans’ lives.

It boiled down to matching the research method to suit the charity, and most importantly the circumstances of the person who was going to actually be using it, something which is true whether researching remotely or in person.

Just like with the WellChild WhatsApp diaries, by ditching the tech you can yield far better insights and crucially, create a better digital experience for everyone.

5. Don’t overcomplicate remote usability testing

There comes a stage in each digital project when you’ve got a prototype, and are looking for feedback into how–and if–your tool will be used in the real world. This is where usability testing comes in.

Often, before you even have a working prototype, you’ll want to test the proposed categorisation and ‘findability’ of your product. Tree testing (explained excellently here) is a good choice at this stage. Tools like UserZoom have fully remote capabilities and can do loads of different tests, including tree testing.

Once you’ve got a prototype you’ll want to see how users interact with it. Nielsen has a comprehensive list (as of 2019) of remote usability testing software and what types of data they can collect. Obviously all these are digital, so are only appropriate for populations with the right kind of tech.

This all may seem daunting if you’ve never done it remotely, but you don’t even have to go out and buy fancy software. Don’t overthink technical solutions to things; you really can go as lo-fi as you want with remote usability testing.

It can be as simple as emailing screenshots to discuss later on FaceTime, or even sending them paper versions through the post! You don’t always need to be testing a fully-responsive prototype with expensive UX software.

6. Be aware of what could go wrong

Nothing worth having comes easy. There are some challenges with remote research processes. This is especially true over the past year, where charities have had to adapt to these processes rather suddenly.

Make sure you plan ahead for any potential hiccups. Here’s a quick run down of some challenges we’ve seen this year:

Dropouts

On first inspection, finding participants for your remote research or usability sessions seems easy; a virtual research session is less of a big commitment to participants, right? In reality, a virtual session may be easier to gather mass interest for, but it’s also easier to cancel on.

You can try to mitigate this by offering some kind of incentive to participants. If your budget allows, you could offer vouchers as a reward for people’s contributions. Alternatively, schedule reminder emails for your participants, and give them an opportunity to reschedule on the day if they can no longer make the session.

Fear of losing control

On occasion, we’ve seen a charity have concerns about prototypes being hosted on the internet during usability sessions; what if the link gets shared around, or if screenshots end up in the wrong hands?

Whilst these are valid concerns, there are ways to combat them. One example is by creating a prototype link which expires after a specific amount of time. However, it’s worth considering that these worries from your stakeholders could delay or even put a stop to remote usability testing.

Less visual cues

Obviously, with a phone call–or even a video call–you’re missing people’s body language, something that can articulate people’s feelings better than words alone can. You therefore need to focus harder and be faster to jump on the opportunities their verbal cues provide during the conversation.

You’re also lacking the insight into their home context, unless you specifically structure it into the research by asking them for something like a FaceTime tour, filling in a diary, or sending pictures.

Time consuming tech

For later stages like usability testing, you have less control over the technical set up. While it’s good for representation for people to use their own devices, it might mean spending a bit more time explaining to them how to access the test materials. Your method needs to flex to their technical abilities, and what tech–or lack of–that people have access to.

7. One last thing… Triangulate!

When you’re learning about your audience, it’s important to mix methods and layer qualitative with quantitative data. A deep, anecdotal, conversation with an individual can help explain a broad trend found in a survey, and a broad trend can point you to the questions you should ask individuals. One without the other is far less reliable.

It’s all the more tempting to reduce the amount of research you carry out when you’re working remotely, and easier to lean on a smaller set of methods. It doesn’t need to be expensive, and triangulating insight reduces the chances of investing in the wrong solution.

Try to avoid viewing quantitative research (like survey data or analytics) as ‘the empirical truth’. Your quantitative data is easily biased by what you choose to measure, what you’re able to measure, and who you ask. At the end of the day, we’re all human; we’ll never get a complete, perfect picture.

Vary your methods, reflect critically on your work, and continually learn about your users. Only then can you begin to create truly life-changing digital experiences that keep on improving; becoming fairer, more accessible, convenient, and efficient.