Future tech trends for charities to know about

What the heck is Blockchain? How is AI relevant to our charity? What are machines spending so much time learning? We wanted to share with you what these buzzwords *actually* mean, how the third sector is using them and what social impact is being created as a result.

Tech for Press

First things first, something we see often is ‘tech for press’. We are talking about those organisations who are first to jump on a technology trend, create something using that technology, share a press release to international media and then generate exposure for their brand with the intention of raising more for the cause.

One example of this type of digital adoption comes from a charity which created a physical donate button to be installed in family homes allowing people to press it when they felt like donating to the cause. In reality, who do we think flippantly decides to donate during the washing up? If only it was that easy.

However, early innovations certainly generate press attention and often have a positive impact on that charity’s brand awareness and therefore fundraising, but what we think is more exciting is that we’re starting to see technology make a real impact to service users.

Real Impact

At the Charity Digital Conference 2018 in London, we heard from Dan Papworth-Smyth who is new to the team at Breast Cancer Care. Previous to this role Dan was at Teenage Cancer Trust when they were trialling an initiative called ‘Tap to Give’. Essentially, a reimagining of the charity collection tin in the age of contactless cards. You wave your credit card or tap your smart phone and donate the amount shown. However, these contactless donation boxes can also trigger other information once you’ve donated. For example, the box can show a ‘Thank You’ video from a service user as soon as you’ve donated, which we think is a nice evolution of the charity fundraising box.

Some charities are getting pretty hardcore with this, to demonstrate there’s an example from Habitatmap. AirBeam is a two hundred dollar box which measures humidity, particulate matter and temperature in the air, and by carrying these boxes around, citizen scientists and changemakers can basically see live maps of air pollution in cities. The data collected can then be used to campaign and inform for policy changes. Habitatmap have actually designed and made this themselves which is interesting to see a non-profit doing. This was funded through a crowd sourcing campaign – another consideration when trying to fund this type of digital work.

Generally, across the industry, factories in China are churning out more and more connectivity chips, sensors and actuators. What we can take from that is that these internet connected devices are here to stay and there are more and more on the market as it becomes an even bigger part of daily life. I even have an Internet of Things kettle which has profoundly affected my life.

Virtual World

Next up, the virtual world.

Nope, this is not a scene from Black Mirror but a photo from the Facebook developer conference where Mark Zuckerberg said that Facebook want to put one billion people in virtual reality (VR) by 2020. Hopefully they’re asking permission for this.

Social networks are investing in new technologies to own more than a little distraction of your day, but instead to own an entire virtual environment in which you socialise.

What this does mean is that tech companies are pouring huge amounts of money into making virtual reality a ‘thing’. By in large, this is happening in two parallel streams.

Firstly we’re seeing huge adoption amongst computer gamers including the adoption of very sophisticated virtual reality headsets which show more lifelike images, contain movement tracking, motion sensors and give the user a real sense of actually being there.

However, not a lot of people can afford a £600 headset so we’re not able to reach a broad audience that way. On the other end of the scale, there are things like Google Cardboard – devices made from cardboard that cost around £5 – where you click a smartphone into the headset and the movement sensors in the phone do a decent job of tracking where you move your head to make you feel like you’re in a virtual reality.

It’s nowhere near the same experience as with the pricey gaming headsets, but it’s nearly good enough.

In the charity space, one of the first examples we could find of this technology being used was by Charity:Water – an organisation which appears to be first to the party with a lot of new technology. Charity:Water held a gala dinner in New York, and instead of playing the big, emotionally impactful video on a screen to encourage donations, everyone was provided with headsets enabling them to experience a 360 degree video of what it is actually like for one of their service users to have to go and collect water to provide for their family. The charity raised more money than ever at that Gala which they attribute to the fact that VR creates a greater sense of empathy.

Now an example which is a bit closer to home and more down to Earth but still an amazing use of VR from The National Autistic Society. They put together a VR experience called ‘Too Much Information’. Again, rather than being a virtual world where you can walk around and experience whatever you want, they created a film to help you experience life as a child with autism walking around a shopping mall. Experience flashing lights, distorted noises and strange sharp sounds. Of course it’s not possible to adequately simulate what it must be like to step into someone else’s shoes with a particular condition, but it goes someway to building a bridge of empathy between the general public, donors and service users. Other examples include a 360 degree video on Facebook created to show what it is like to live with dementia. It appears there is an emerging trend in providing a VR experience to help you empathise with what a charity is advocating for.

Conversational Interfaces

It’s worth treating this topic with a little bit of cynicism. About 3 years ago, I spent a lot of time, reading about these things called ‘Chatbots’ and how they’re going to change everything and how everyone will be using them.

One interesting example of the use of a Chatbot is a website created by a guy called Joshua Browder who at the time was 19 years old, living at Stanford. Joshua got a parking ticket and we’ve all probably experienced getting so angry about something that your reaction becomes completely disproportionate to the circumstance. Well, Joshua’s reaction to his parking ticket was to build an Artificial Intelligence (AI) robot lawyer that would allow anyone to challenge parking tickets. It’s aptly named ‘DoNotPay’ and today, hundreds of thousands of people use this tool to get out of paying parking tickets in the U.S. Got to love his commitment to the ‘cause’.

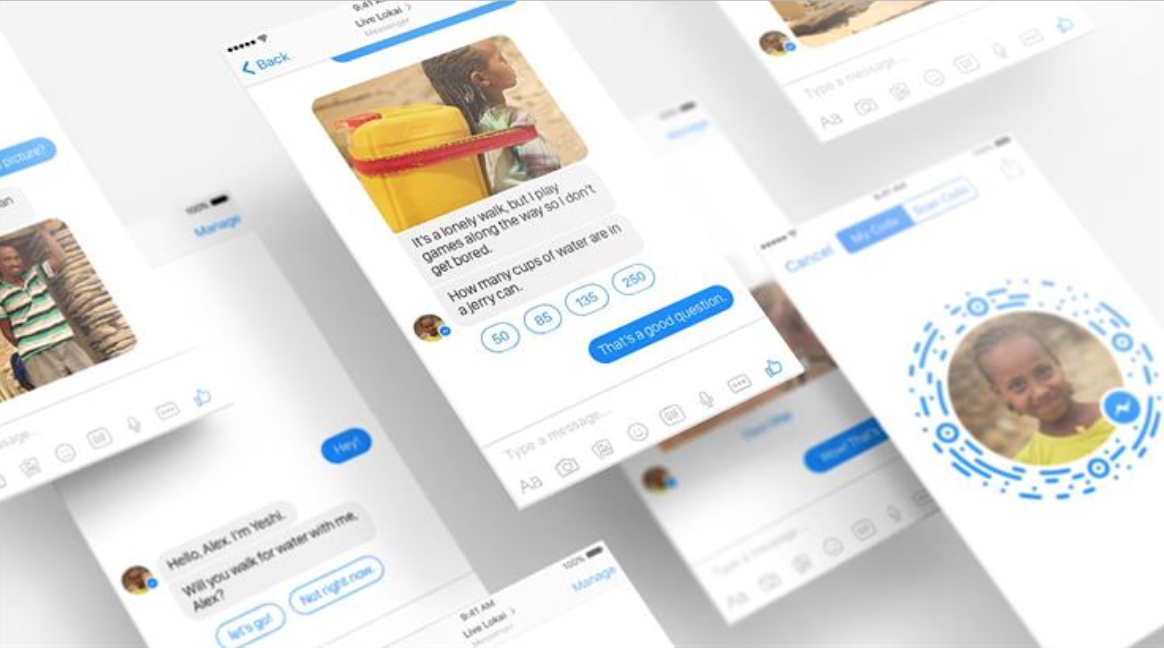

Walk With Yeshi

Charity:Water was one of the first charities we found to start using Chatbots, creating an experience called ‘Walk with Yeshi’ where you have a conversation with one of their service users. Join Yeshi on the long walk to collect water for her family through a conversation with her – as if you were messaging a friend. Ask Yeshi questions and she gives facts and talks about aspirations. This was popular for Charity:Water raising a lot of money. Now think about the Chatbot phenomenon and consider the following graph.

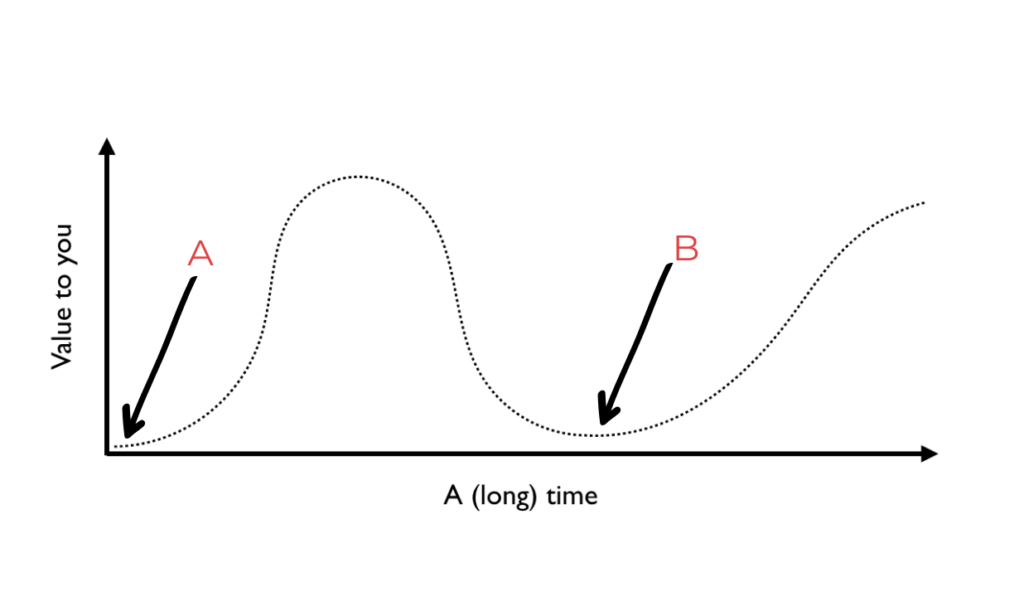

Arrow A a piece of technology being invented, like Chatbots. The X axis is time – a pretty long time in this case – usually a number of years, and the Y axis is the value added to you, as a charity, through potentially adopting that technology. Initially, there’s no value in adoption. It is enormously expensive and no-one really knows what it is yet or what it could mean.

However, there comes a point where there’s just enough public consciousness about this new tech that’s out there, like Chatbots, that if you were to do something, it wouldn’t really do anything for your service users but you might get a lot of articles in newspapers and you can see that some of the charities that we’ve mentioned, like Charity:Water use this process like a cookie-cutter. Every time a new technology comes along, they’re quick to jump on it, press release it, get a load of attention and raise money off the back of it.

At point B, there is this dead zone that occurs where the world waits to see if this is actually going to take off and change everything, and I feel like we’re here with Chatbots right now. It’s quite hard to predict whether these things will make the earth shattering change that they were predicted to. There’s a report from Gartner that said “By 2020, the average person will have more conversations with bots than with their spouse.” 2020 is not so long way away so that would be a rapid (and pretty depressing) adoption of this technology considering most people can’t even name a single chatbot.

A few charities have started using voice. At Reason Digital, we have done some work with Age UK to produce an Alexa skills. Cancer Research UK have created something where you can maintain a dialogue with your Amazon Alexa to track how much alcohol you are drinking – given Alexa doesn’t have a camera yet she’s trusting your honesty. British Red Cross have done something where Alexa can read First Aid instructions out to you, so if you’ve got your hands full with an incident, then you can be talked through instructions.

At Google’s developer conference a few weeks back, Google Duplex was introduced. This is their voice assistant which can call people up on the phone, to complete tasks for you. The CEO of Google demonstrated live on stage with the example of making an appointment with a hairdresser. He played the call. The phone rang the hairdresser, pretending to be a human, having a dialogue and then booking the appointment.

At one point, the hairdresser assistant asked, “Would you like – Tuesday or Wednesday?” and Google’s assistant replied, “Errrrrr… I think I want Wednesday.” Google Duplex threw in some conversational fillers to appear more like a human. Many people found it as creepy as they did impressive.

Google have said that they aren’t going to implement the technology in this way. They want to make it clear to people on the other end of the phone, that it is a robot not a real person. However, you can’t help feel that it is a little scary that someone could have an appointment booked with them and not even be aware that they’re talking to a robot. God help us when the PPI cold callers get hold of this tech.

The difficult thing about AI for charities is that there is such a callous gap between the resources of someone like Google or Amazon, compared to that of a charity. There is potential to see more development on this, but only when larger companies start to work with us. There is hope, though. Many of these companies are making AI tools available to developers, and some are encouraging charities to reach out to them for support with using their AIs.

Machine Learning

Let’s start with the important stuff. On the television series, Silicon Valley, one guy creates ‘Hotdog or Not?’ – an app which tells the user whether the thing they’re pointing their phone at is in fact a hotdog… or not. On the show it became very popular, and someone in the real world, saw it and made it. Obviously.

You can download it on your phone and play with the ‘Hotdog or Not?’ app. It is ridiculous, but also a good example to give people a feel of the types of problems AI and machine learning is really good at, right now. It is good at taking vast sets of information and noticing patterns in order to be able to apply that again.

The creator of this app obtained thousands of images of hotdogs, put them through machine learning and the machine learning was able to distill the ‘essence’ of a hotdog into a kind of model. Then, when shown a hotdog again, it could tell you whether it was indeed a hotdog or not. No one programmed (or explained) to the app what a hotdog is or looks like, it figured it out on its own after “seeing” a large amount of sample data.

This may seem like a really frivolous problem but actually there could be problems that the charity sector is facing that could be solved with that same kind of image matching.

For example, we work with Age UK. They have a product called ‘Call in Time‘. This is a befriending service, where older people are connected to volunteers over the telephone.

Currently, for safety reasons, a human has to listen to each call to check for safeguarding reasons. Some of these calls are long, which is great because people are making friends, but it also means that it can take three hours for a staff member to complete that check.

What we’ve been experimenting with at Reason Digital, is using Amazon’s AI platform to transcribe those calls into text, and then scan that text. We can then check for any problematic words in there such as ‘credit card’ or ‘phone number’ and we can also rate the sentiment of the language, for example, is the call consisting of negative language or is it more positive?

The difficulty is that when using AI, the technology is 90% there, but that last 10% is where it really needs to be to make the difference. Practically, one of the problems we’re finding is that Amazon’s machine learning algorithm which converts speech into writing is not very well trained in understanding older peoples’ voices. Their data set didn’t include lots of older people, in particular, it didn’t include lots of bad recordings of older people on telephone lines, so it makes mistakes and gets things mixed up some of the time. This is a practical example of the power and the limitations of AI.

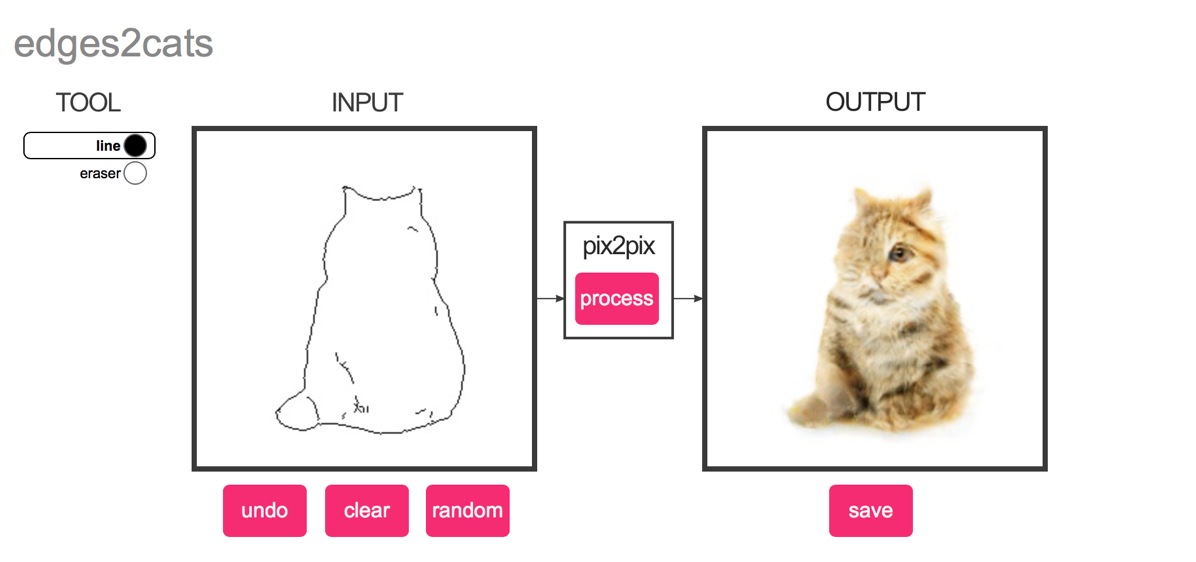

Another thing that AI can do is, in addition to taking information and understanding it, it can actually be creative and make things. There’s this web app called ‘Edges to Cats’. This algorithm has been trained to understand the essence of a cat. Why? So that you can draw a shape of a cat and the programme will then turn that into a photograph of a cat. Pretty awesome right?

You can see it has guessed it has one eye. 90% of the way there is not quite enough. You can get crazy and terrifying with this stuff.

Some people are already putting stuff like this to use for pro-social end. Xrapid Group are able to diagnose malaria in a blood sample using machine learning through an iPhone plugged into a microscope. It takes less than two minutes for the analysis to run, whereas it takes up to 30 minutes for a traditional test to be run on the same sample. Pretty impressive.

This is just one of the types of problems that machine learning is good at solving. There is a lot of data out there about what blood looks like with malaria and without malaria, so there becomes a clear pattern to be matched allowing the diagnosis to become a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

A project we’re working on with a couple of charities in the UK is not dissimilar to a platform called Thread – an online stylist. Thread employ five personal stylists and as a user, you register, tell the personal stylists what you like, and then those stylists serve about 500,000 customers with an apparently completely personal experience. The user experience is that it feels like you have your own personal stylist, but of course you don’t. Your contact with that personal stylist is disinter-mediated by a machine learning algorithm.

With this in mind, we’re experimenting with this principle with Parkinson’s UK. Instead of taking five personal stylists, we take five people who work on an advice line or five expert nurses and allow them to deliver apparently personalised coaching service over email to large numbers of people. This can provide an ongoing bed of support and help make that service more scalable, particularly for those causes that affect millions of people since there is an asymmetry between the number of people that can help and the number of people that need help.

Another really interesting example of machine learning that’s having an impact today is a Crisis Textline in the US – a free phone call and text line for young people. The problem they are trying to solve is how to prioritise messages that come through. When receiving thousands of messages a day from young people requiring help, how do the call takers decide how to manage the queue? Who is the biggest priority? What Crisis found was that somebody who mentions the US equivalent of the drug, Ibuprofen, is at higher risk of suicide that someone who actually uses the word ‘suicide’. This is something that we as people would never guess but this is the reality.

In terms of machine learning and AI there is a phenomenal ethical balance to this. This is going to be a huge conversation which reshapes society. There is a ‘Partnership on AI’ which a bunch of the big tech companies have created. They are really keen to hear from charities about different uses of this technology and they’re keen to have case studies and good examples of it being used. If you think you’ve got a cool idea, it may certainly be worth reaching out through the ‘Partnership on AI’.

Personalisation

Just a brief mention now on something that machine learning is just blowing the dust off – the concept of personalisation. Five or so years ago personalisation on the internet was a hot topic. Personalisation is when you go on Amazon for example, look up a book like, ‘How to deal with being dumped’ and Amazon offers you some insight on what else you might like by saying, “People who bought this also bought this tub of ice cream and these Kleenex tissues.”

The idea of it was that if you’ve got enough data you can analyse it, spot patterns and suggest what other things people might want to look at based on what they’re doing on your app or website.

Where this gets more futuristic and more interesting is with the development of sensors in addition to the fact that we’re getting a lot more information about people though their Internet of Things devices. There is very rapid development in sensing technology now, for example, you can detect how much somebody’s had to drink through skin sensors. There was an experiment with one of these sensor technologies a few years ago where I got my DNA sequenced, and you get a tube which you have to fill with spit (which is really difficult, by the way!). Once tested, you’ll receive information on your genetic risk of developing certain diseases. There are all sorts of issues with this; the data set is quite small, it’s pretty much finger in the air stuff. But, what this made us think about is the fact that these tests are getting cheaper and cheaper because the science is getting better and better. One day in the not so distant future, we’re going to wake up in a world where parents routinely test their children. As a parent you don’t want to know, but it’s good to know because if there are risk markers, you can adapt your child’s lifestyle to counteract these risks.

What’s interesting to fundraisers is how this type of information could reshape the fundraising landscape, particularly for medical research companies. The pattern right now is we get to the age of 60, get diagnosed with cancer, your friends raise money for cancer charities. But what if you know from the moment you were born that you’re likely to get this particular form of cancer. How would that reshape your relationship with charities and in particular which charities you choose to support? This should be interesting.

Service delivery

2018 is the year of charities not only asking for money online but also delivering services online. We’ve already mentioned a little bit about the ‘Call in Time’ service from Age UK, but that is a great example of using a wonderful piece of technology – the good old fashioned analogue phone and enabling Age UK to provide a scalable service. We’re seeing a lot more job advertisements go out about this, a lot more briefs come in as charities are working to find digital ways to have a social impact, rather than just ask for cash and talk about stuff.

Blockchain and Transparency

Blockchain is a really interesting one. On the innovation curve, it’s really still quite unclear about whether blockchain is going to change everything in the world or just be this thing we all recall in 10 years.

Blockchain is interesting in the sense that it is effectively a trick of mathematics whereby you can put a database out there and if it gets tampered with, it becomes very obvious. This means, amongst other things, that the database can be decentralised. You can create a situation where everyone can have absolute trust in a set of records because they know that if someone tampered with one of the records, it just becomes blindingly obvious because of how the maths works: the data doesn’t validate anymore. It also means that you can create what is called ‘Smart Contracts’ and these contracts are bits of computer code that create an action, for example if the temperature in Manchester gets higher than 30 degrees, then give £20 to a climate change charity and that can then be executed in code. There are a few projects, some local, some international that are experimenting with this process in regards to the transparency of the impact that charities have.

An example of this is ‘Alice’, an organisation that have had a pilot with a homeless charity in London called St Mungo’s to try and track a donation from the point where it is given, all the way to when it impacts the life of a homeless person. They do this through using a blockchain record resulting in the inability for that charity to forge, tamper or interfere with that data.

There are practical problems with these approaches because at some point, someone has to say “We did A, and we had B impact”. But unfortunately a human can just lie about that fact so it’s great that the digital records are tamper proof but the input data is still open to fraud. Better sensors, and better machine processing of things like documents and videos that could prove something has happened could be a fix to this.

What we think is most interesting to take from this, is less the blockchain element, and more the fact that the public are increasingly interested to see that their money gets to where it should go. As charities we’ve maybe not been great at educating the public about how them giving money works in reality.

Take this example – Charity asks for money for malaria nets. The charity has not told the potential donors that the company that makes the nets gives them for free or at very low cost, and what the charity actually needs the money for is to design a logistics database so that they can distribute the malaria nets to the right people. Because, let’s be honest, that’s too complicated.

There is increasing need for trust from the general public. Watsi (a start-up in the U.S) have a website where you browse people in need of funding to have medical procedures. You can choose exactly who you want to donate to and the money goes straight to the person. This is something a lot of charity professionals shy away from. Firstly it can be challenging to commit to where the money is going but also it’s not necessarily ethical to have a beauty parade around who gets what money. Unfortunately, in the current climate, donors want this and the charity sector is going to have to come up with some sort of reaction to this.

The thing that blockchain might help charities grapple with is the transparency of impact. At the very least, it’s creating interesting conversations around it.

The Data Crisis

Most charities are reporting massive dips in their contact databases since GDPR day.

Users have more power than ever to force organisations to remove or amend their data. We now need to think hard about offering them value in every communication rather than just telling them what we want them to hear.

Interestingly, even before and after GDPR we’re seeing more cases being brought by the Informations Commissioners Office (ICO) where charities are being fined for misusing predominantly supporter data but also service user data.

The ICO publish infographics about the 3 reasons they’re most commonly suing charities because of:

- Using wealth ranking services

- You give an email address, but they look up your phone number from a different data set – a common breach

- Trading your donor data, perhaps with other charities

The other thing that we’re seeing in terms of a data crisis is data security. So even if you’re following all these regulations, your website or database can get hacked and you can still get fined.

On a very serious note, the British Pregnancy Advisory Service a few years ago were fined £200,000 when a hacker accessed their data about people who requested a callback about abortions. The hacker was actually a pro-life activist so was doing that for very political ends.

There seems to be more and more of these things happening and since May 25th, the ICO has more power than before.

Backlash and how to Deal with it

As we’ve mentioned, it wouldn’t have escaped anyone’s attention recently that the public are really starting to think deeply about what data they put on these platforms and how they use it. It’s already challenging to reach people on these platforms. Facebook has made their algorithm increasingly difficult for organisations to actually get their message out there resulting in organisations needing to spend more money on Facebook advertisements just to keep the same level of cut-through they enjoyed previously for free.

The secondary issue is the public retreating from these platforms due to concerns over privacy although the data we’ve found is fairly mixed. On one hand, we see some reports that Facebook’s growth rate is just as strong as ever, but we see other reports showing that Facebook usage is down.

I predict a luddite movement. Not too dissimilar from the one we’ve seen with vinyl where people started rebelling against mp3s, Spotify, Apple Music and so on. I think we’re going to find a group of people who will try to reconnect with physical reality and that could instigate a backlash against tech. Maybe it’s time to consider whether we have any of those people in our target market audiences?

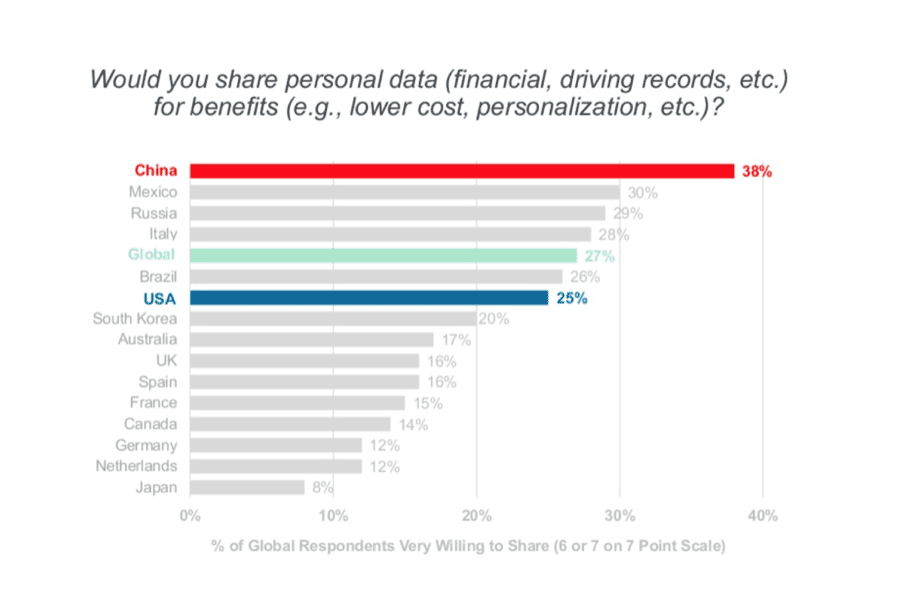

The statistics around this area are interesting. Here’s a survey around whether people would share their personal data for benefits such as money. Only 16% said ‘Yes’. What does this say? Well, if your personalisation strategy relies on asking for a lot of information from people, you may have to rethink that. China has highest amount of anyone responding with a ‘Yes’ but that’s still only 38%.

The survey also asks what actions you are taking to address data privacy concerns, if you have them. 64% of people deleted or avoided certain apps, 57% adjusted their mobile privacy settings, 28% disabled cookies, 27% stopped visiting certain websites, 26% of people read privacy agreements and 9% avoided buying certain products that made them give up their data.

We have to think hard about what data we’re capturing. We can’t buy lists of data anymore and simply asking for information seems like less of a strategy than before. With this in mind, the next trend that comes in is focused on thinking more about how we collaborate with innovators and creators. The reality is that it is expensive to maintain an audience and a database and a potential solution to that is to collaborate more with people and make that an investment. It could be the classic YouTube influencer who built up an audience that you could also reach, risk free.

On the other hand, there are digital innovators. As an example, take these two websites above – ‘I Want Prep Now’ created by activist, Greg Owen and ‘Prepster’. You’ll notice the first one has a Terrence Higgins Trust logo on it. A bridge has been built connecting Terrence Higgins Trust to Greg Owens and as a result they started having the conversation – “Can we help you do this? Can we help you to be more sustainable and robust?” And this is the result of that collaboration .

Rather than thinking, how do we solve all these problems? How do we deal with all this data? Instead, we need to be thinking, are there people out there that are already innovating?. Instead of feeling threatened by that, we could just build a bridge and show what we can offer and bring to the table – our expertise, our service users, our safeguarding, our knowledge, our care.

This is something we’ve experienced with an app we’ve created called Gone For Good. We’ve managed to get a group of charities to come together and work with us on this app. The app itself lets users take a photo their items from their own home and offer it to charities who will come to pick up the items for free to take it to a charity shop to be resold.

What we’ve learnt from that process is that if from an innovator’s perspective, you go knocking on charities doors, telling them, “I’ve got this great idea, I’m thinking of doing X, what do you think?”, then you’re not going to get very far. Rather than asking for their interest, approach the conversation more from the angle of, “I’m just going to go and make this thing over here, you either want to be a part of that or not.” Then once you get one major charity on board, e.g. Cancer Research UK which in our case was the first charity to see the vision and the value, then others may follow.

How could charities make it easier to learn about and contribute to these innovations and how could charities be more receptive to technology? How can charities share the challenges and opportunities they face in a way that inspires innovators to play with solutions and responses to them?

I don’t think it’s about hack days, at least at first, it’s just about keeping your ear to the ground, being in contact with people about ideas and that can lead to a collaborative innovation and partnership. At the beginning of the Gone for Good work, charities were concerned about sharing space with their competitor charities in the same app, thinking, maybe we should be making our own app? Now, not only are they comfortable with that, it’s actually allowed us to raise an extra million pounds for them using the app. We’ve grown the pie, instead of worrying about the size of any one person’s slice.

There is even conversation of them sharing vans to use to collect goods. Vans can be a nightmare and when there are eight charity shops in one little town and they all each have their own van, it just doesn’t make any sense.

It’s amazing how far you go if you leave the door open to people who are innovating.

Final Thoughts

We’ve got to be aware that there are only a certain amount of people out there in the world who can make this sort of magic happen with tech and actually do it well. Consulting with users, managing the process properly and getting results. My last kind of slightly worrying prediction for you is that these people will become incredibly high-demand over the next few years as more and more organisations start to try to hire and work with those people. We would recommend starting thinking now how you can make your organisation attractive to people who have the skills to leverage digital for charities.

We really need, more than ever for charities to be more involved with tech. By lifting our digital capability we can do more good stuff with this amazing technology rather than make the world a little bit worse with it by accident.

More tech trends this way...

-

Can AWS Wavelength help charities with AR and VR?

Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) might be exciting for gamers, but charities should also be feeling the buzz.

Find out more

-

Three creative tech solutions brought to life in response to the pandemic

As a social enterprise, we’ve learnt some valuable lessons over the past few months when it comes to providing digital solutions for good causes. We’ve had to move quickly to give our support and add value where we can during uncertain times.

Find out more

-

Twitch for charities: Supercharge your digital donations strategy and level up using Twitch

With charities being set to lose more than £4bn in just three months as a result of COVID-19, the fundraising landscape has changed drastically for the third sector. And it feels like it happened overnight. With digital fundraising hastily climbing its way to the top of the priority list as events are cancelled all over the world, there are platforms out there which charities may have never interacted with before, that are now becoming an essential part of fundraising strategies. One of these platforms is Twitch.

Find out more