Are donations in our DNA?

Something strange is going on. Millions of people are filling a test tube full of spit and posting it to California. That’s because bio-science companies there are making them a staggering promise: send us your cells, and we’ll tell you who you are.

It’s called “at home DNA testing”, and it’s hitting the mainstream.

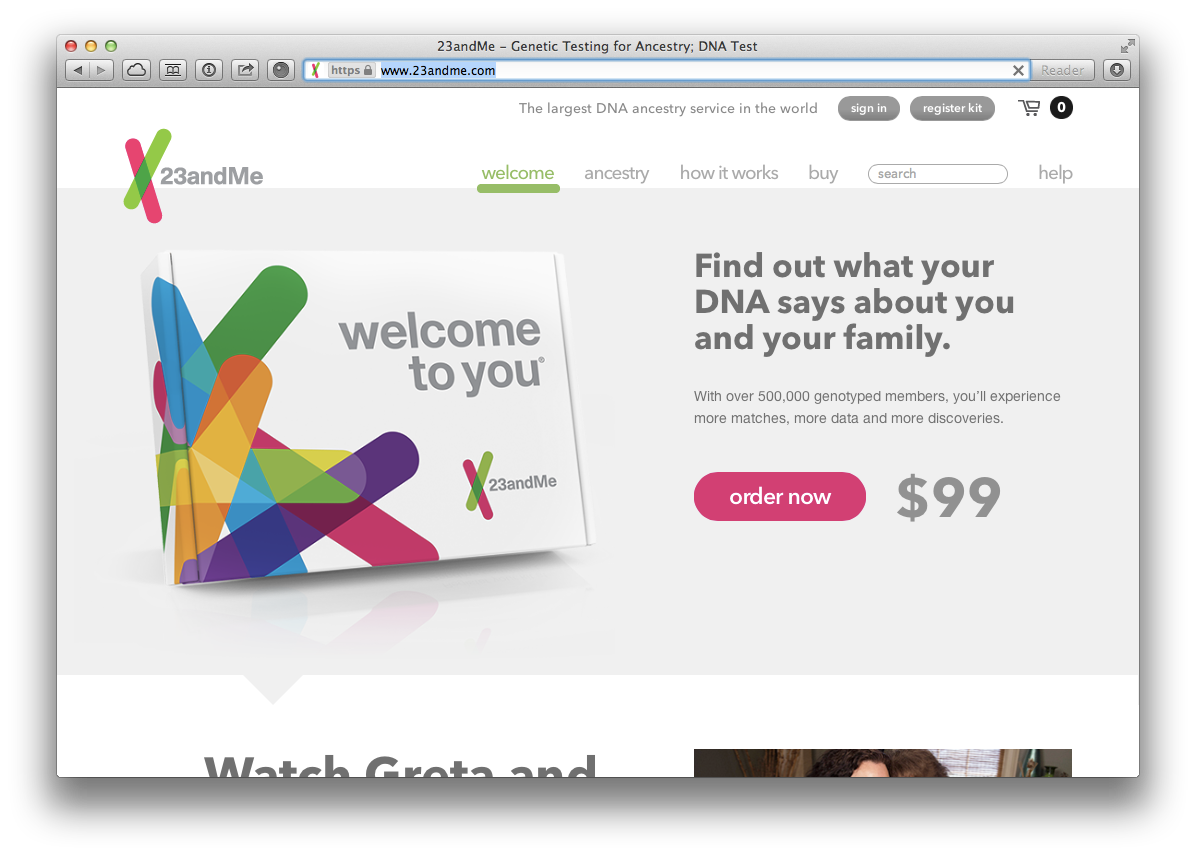

It costs just £125 to take a test with the most popular at-home service, 23andMe, who have just expanded their offerings into the UK.

For many the motivation is in delving into their ancestry – especially for the huge number of Mormon customers of the service. Not only will you gain insights into your genetic makeup – including your percentage of neanderthal ancestry – but it also the service offers to connect you to other testers who it finds a family relationship with.

For others, though, health is the driver. And DNA testing represents darkly tantalising prospect of gazing into a crystal ball to see a glimpse of your medical future and even, perhaps, your death.

Whilst the relationship between family ties and DNA is well understood, the relationship between your DNA and what might kill you is not. Early research has provided some clues; enough to claim that these services can show you some diseases you’re more at risk of.

We’re just at the beginning of a new frontier in medical research enabled by the ease of availability of these tests.

Having DNA samples of a dozen people suffering from a particular condition is one thing, and this can establish a link between the code in your cells and your predisposition to disease.

Having a million genetic records and a survey of each individual’s health history is a whole other ball game. ‘Big data’ techniques are being brought into play, finding connections and relationships with artificial intelligence instead of by trial-and-experimentation by humans.

This is very quickly and quietly becoming the largest medical endeavour in human history. And, as demand and technological progress drives down the costs and the accuracy of the results, at home DNA testing will only become more popular.

It’s easy to imagine a not-too-future world where the majority of people not only test themselves, but routinely test their newborn children, to attempt to better shape their lifestyle around their health risks.

We’re not yet in that future. Yet the early results of this new frontier are available to those taking at-home DNA tests today; in the form of a cold, terrifying percentage score for a list of hundreds of diseases, conditions and traits.

I think this is gives us an early warning of something that might change our relationship to charities and good causes. I set out to find out more.

–

Clicking through the sign up process on the 23andme site I wondered what motivated others to take the test.

For many, no doubt, it was discovering ancestry, predicting health issues, connecting to biological family, discovering your racial make-up, or even just taking part in something cutting edge. I had an altogether different concern, though.

It took weeks for the kit to arrive from the Google-backed company in sunny Mountain View, California to rainy Manchester, England.

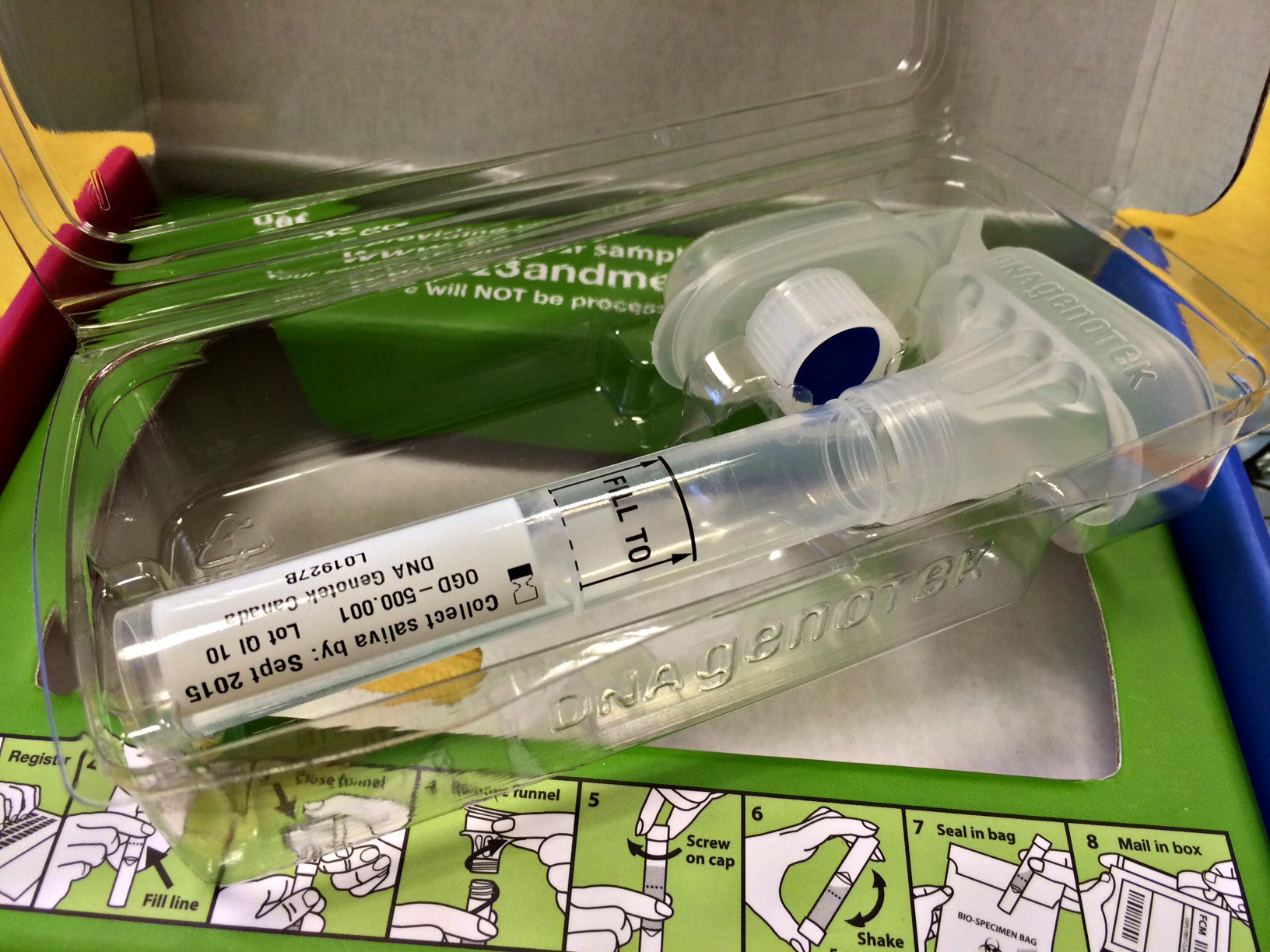

The process is as simple as it is surreal.

Step one is to fill a test tube with your own spit.

I’d never tried to fill anything with saliva before, and it’s actually surprisingly challenging to make so much of it on demand. I avoided drinking for a couple of hours, lest they tell me that my ancestry points back to tea fields in India.

Tube full to the line I clicked the gap shut, releasing a compartment of liquid into the tube, a ‘buffer’ chemical that would stabilise my DNA for the trip back to the lab.

Tube sealed, I took it, along with various paperwork, to a airmail collection facility in a rainy industrial estate in Trafford for onward travel back to the US.

Back at the lab my DNA was to be amplified, or copied, millions of times until there was enough of it to be passed picked up by a ‘sequencing machine’ containing a new electronic chip designed to read genetic code. This is the invention that makes all this possible.

A ping from my inbox seven weeks later alerted me that this process was complete.

I was a click away from finding out what I had every potential to die from. Welcome to the future.

And the results..?

–

Some results of at home DNA tests are clear-cut, and reliable. The DNA in any cell in your body contains a simple coding that dictates if you are to have hard or soft earwax, or if your urine will smell different after you’ve eaten a lot of asparagus.

The less clear-cut results relate to more serious matters. Your percentage risk of developing a heart condition, breast cancer and even, the service claims, Alzheimers and Parkinsons disease.

Without any information about your lifestyle, or even clues about the causal relationship between these DNA markers and conditions, it’s hard to know the accuracy of these results.

The majority of obese people may often have a suspiciously frequent pattern of DNA markers in common, but perhaps a test of a person’s diet or activity levels might provide bigger clues.

For me, these results were now personal, and in spite of the caveats and uncertainties, I was compelled to press on and see my results.

–

Ancestry felt like a gentle start to exploring my genetic code. I was momentarily surprised to discover my 0.1% Sub-Saharan African ancestry, before being hit with the profound realisation that every human being can trace their origins back to common forebearers there.

It was where my code was different, potentially haywire, that drew my attention next.

Could an unfathomably long piece of text made of 4 simple letters ‘A, C, G, T’ hang over my head and worry me for the rest of my life? Would it change my lifestyle? Would it be a technological momento mori, spurring me on to make the most of life?

I clicked the Health Risks report.

Atrial Fibrillation were the first words I saw on the page. I’d never read those words before.

A second or two of Googling led me to a charity that explained the 23andme service would give good odds on me developing a heart condition that causes an irregular and often abnormally fast heart rate.

It claims I have a 33.9% risk of having this condition, which is 1.25x the average risk of 27.2%. While this wouldn’t put me at direct risk of death per-se, it can increase risks of strokes and heart attacks.

I quickly took in the other results. Prostate Cancer, Gallstones, Chronic Kidney Disease, Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Stomach Cancer. These are my ‘elevated risks’, and are scored with a ‘confidence rating’. Only those with a 4 star rating give added detail.

| Name | My Risk | Average Risk | Compared to Average |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 33.9% | 27.2% | 1.25x |

| Prostate Cancer | 23.5% | 17.8% | 1.32x |

| Gallstones | 11.1% | 7.0% | 1.58x |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 4.2% | 3.4% | 1.22x |

| Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) | 0.43% | 0.36% | 1.21x |

| Stomach Cancer (Gastric Cardia Adenocarcinoma) | 0.28% | 0.23% | 1.22x |

Some conditions naturally have connotations with your quality of later-life. These conditions are so worrisome to many that they are hidden on the results sheet.

The results all come without clues of when in your life these things might strike. Could it be the inevitable and certain cause of death after a happy, healthy 101 years? Or something already flaring up inside you? Your DNA, and 23andme, can’t tell you. At least yet.

I hovered my mouse over ‘Alzheimer’s Disease (HIDDEN)’. In for a penny, in for a pound, right?

“Are you sure?” the site checked.

“Yes” I clicked.

“Are you absolutely sure?”

“Yes”

“You can’t unknow this.”

“Yes, yes, yes, I know.”

And the reply? I’m less likely to develop Alzheimer’s, with an estimated 4.3% risk compared to the average male risk of 7.3%.

–

Most experts agree that Alzheimer’s is not a diseased caused by genetics but one that is merely influenced by it. A gene called APOE e4, in particular.

Knowing things – or thinking you know things – about your health like this can have unexpected negative results. It’s counter intuitive, yet it turns out that being tested for every possible ill is actually more likely to hurt you, than help you be healthy.

There’s no real way to avoid Alzheimer’s, so there’s the stress of worrying about it all your life. Stress that not only affects your quality of life, but can affect your physical health too.

Worse still, some will undergo unnecessary, risky invasive surgeries and radiotherapies to prevent or remove cancers that wouldn’t have developed quickly enough to impact them during their lifetime.

There’s something good that could come out of this seemingly inevitable DNA testing phenomenon, though. A good that that doesn’t even need the results to be all that accurate.

–

I breathed a sigh of relief, health risks report still open on screen.

I now knew what it was like to see the results of a test that claims it knows your risk of developing things that might kill you.

In some ways it seemed I’d been dealt a good hand: I knew before I started out that I’d rather live thinking I had a risk of expiring from something that affects the body, rather than the mind.

Yet, somehow, I found my results cold comfort.

I took the elevated risks seriously, and yet talked myself out of relaxing about the reduced risks – the science is just too early days, I rationalised.

So was my outlook on life being reshaped?

The truth is, that didn’t matter to me just then. I’d already got my answer to the question I set out to answer.

You see, I’d instinctively spent the last 30 minutes searching for information about health conditions I previously hadn’t spent 5 minutes thinking about – let alone felt any affinity or connection with.

The websites my searches led me to were often charities. Charities that seemed somehow to be more relevant to me now than mere minutes ago. Charities I’d never donated to.

Charities I now recognise, I now follow on social media, and that I would soon become a supporter of.

Now imagine hundreds of millions of people doing the same.

–

The ‘big 3’ UK health charities – Cancer Research UK, MacMillan and British Heart Foundation – pulled in £1,096,131,000 of voluntary income in 2012 alone, and in 2014 medical research charities overtook religious charities as the nation’s favourite cause.

It’s easy to see why. Not only are these the charities that so often spring to mind when someone is looking for an excuse to run a marathon or skydive, but nearly two thirds (61%) of Britons name personal experiences as the factor that drove them to give to charity. It’s a sad fact of life that cancer and heart conditions affect a majority of us, either directly or through family and friends. With people living longer, it’s inevitable more and more of us will be in this position.

DNA testing will likely further this trend, and it’s unclear if this would mean more money for medical research and support charities on top of existing donations, or a shift away from cats, guide dogs and international aid.

There is a clue in the very nature of the test. Many of the diseases these charities exist to support strike later in life. They limit life, and work, and the disposable income of the individuals and families they affect. Understanding and, crucially, feeling a risk of facing disease earlier in life will likely result in people giving earlier in life, and therefore over a longer period.

The flow of donations could be reshaped in 5 – 10 year’s time.

It’s hard to predict if the results will make charitable giving more fair, or meritocratic, but one thing is for sure: some charities will do better than others from this shift.

–

On a day where another email pings in telling me about the fact I like coriander, after another artificial intelligence hails a new genetic code matched with an inane survey question, I hatched a plan: I’d stop thinking about it and try living this change myself before it hits society at large.

I decided I would give over a year’s worth of charitable giving to my DNA. I’d stop listening to the moving TV ads, the imploring newsletters: I’d find the answer of how much to give to which causes within myself.

I divided £1,000 between seven charities based on the increased risk I had in developing conditions relating to their work and research according to the genetic test.

| Condition | Organisation | Donation |

| Gallstones | Core | £355.00 |

| Prostate Cancer | Prostate Cancer UK | £275.00 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | AF Association | £255.00 |

| Gout | Arthritis Research UK | £75.00 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | Kidney Research UK | £25.00 |

| Obesity | Weight Concern | £10.00 |

| Venous Thromboembolism | Lifeblood | £5.00 |

| Total: | £1,000.00 (ex gift aid) |

This wasn’t as straightforward as I first thought, and I got some help from the Reason Digital research team. They helped me weight my donations both towards what the results told me my chances were, but also towards the unique ‘elevated’ risks I had, creating a donation profile as unique as the DNA results. Letting my DNA be the only decider meant that these donations didn’t factor in the perceived seriousness of particular causes too.

I logged on to the websites – many of which I’d already seen when trying to interpret my results – I made the donations and promptly got my card blocked for giving so much to so many different charities in less than an hour.

The fraud team at my bank demanded an explanation before they’d unblock my card. Some twenty minutes later, they were sorry to have asked.

–

Many health charities range from privately cynical about at-home DNA testing, to actively speaking out against it.

Those that do point to the negative consequences of other blanket health testing, such as privately-ordered, full body CT scans – those hurt people. Not just literally in terms of the small amount of radiation exposure – equivalent to an extra 4.5 years of background radiation – but in terms of inspiring worry and sometimes unnecessary treatment addressing issues which would remain symptomless for the rest of a person’s life.

There’s also concern about the management and privacy of this data. So much of our behaviour, interests and intentions are already being mined by advertisers via social network sites, search engines and toolbars. Rationally, this is really what makes us us, much more than our genes.

Yet, giving over our genetic code somehow feels beyond the pale. What if your DNA gets stolen in a hack? Obtained by an insurer that refuses to cover you as a result? Or at the very least used to target ads for asparagus and coriander more precisely.

–

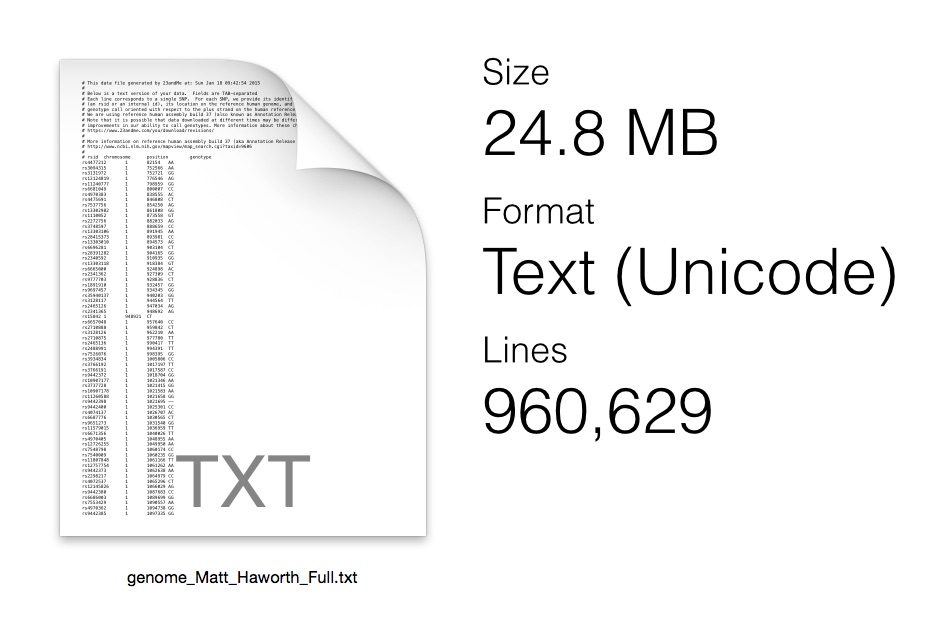

I felt a terror when I saw a button labelled “download DNA test results”. It’s a file on my desktop now – ‘genome_Matt_Haworth_Full.txt’ – slightly less than 25 megabytes, or about half the size of the last album I downloaded to the same laptop.

Seeing that code – the actual letters of it – affected me more than the arresting health risk predictions. Leaps in technology means it’s now possible to look into the smallest pieces of what makes us us. No matter who you are – or even what living thing you are – what you find is a beautiful, simple code of just four letters. You look at it to try to see yourself, but you end up seeing something so much bigger: your connection to life around you.

It all just seemed too profound to let some problems with regulation and privacy law get in the way. The potential so much more tantalising than the pitfalls.

This sense of wonderment broke abruptly to a snort of laughter as I remembered Ben Goldacre’s novel invitation for everyone to find this feeling through science. At home DNA testing wasn’t around back then, though, so he suggested looking at your sperm under a microscope. He wrote how a sense of being connected to something bigger was part-and-parcel with understanding science. What I’m interested in is how can we use that sense of connection to make the world better?

In other words, how we can turn DNA data into donations? Genetics into giving?

Having been through this, I think it’s inevitable that access to this data will change the charitable causes people feel an affinity with, earlier in their lifetimes.

There was just one nagging question left to answer: Is this the way anyone should give?

–

At best it seems that letting your DNA decide your donations is employing enlightened self interest, at worst pure selfishness, overcoming the very meaning of charity in the first place. Isn’t this something else, more watered down, a sort of health insurance? A transaction. Not a donation.

It’s not clear cut.

That personal connection, being moved – or forced – to empathise with others in need, has always been a feature of giving choices. Instead of a moving story, or hearing the experiences of a family member, this just seems to be another, albeit futuristic, way to achieve the same result.

Perhaps one day we’ll know exactly what will affect us in future. If we do, and just give to that cause, perhaps my feelings would be different.

Yet that’s the one thing these results didn’t take account of: the unknown. The results don’t consider lifestyle, or just pure chance. Nothing is quite that finite – even our genetics.

Regardless, one thing that’s for sure is that seeing these results is giving millions a visceral sensation, one that says “these things doesn’t just happen to other people”.

That means we need to ask ourselves the questions, because this change is happening.

Wide scale DNA testing is inevitable and it will affect people’s behaviour, and the charities they support.

So, join in, try it. Donate to a cause that’s close to your…DNA. Or don’t. The choice is up to you. Or perhaps, at least, your genetic code.

Genetic giving

If you want to try it, we’re making it easy for you. Take a 23andMe test and then log into our Genetic Giving website. It’ll automatically translate your genetic results into a recommended donation across a range of UK or US charities researching and supporting people affected by the conditions you may be most at risk of.

Contributors: Matt Haworth / Charlotte Taylor / Dr Paul Joyce / Ian Jukes / Alex Iacobus

Not done learning?

-

Five charities in the pandemic using tech for good

Too often in the media, charities can be painted as rigid, traditional organisations who don’t always adopt new, innovative practices. Ourselves and many others who work with charities to use technology for good, however, see a different story.

Find out more

-

Gender diversity and discrimination: how not to be part of the problem

Being a straight, white, middle-class guy is easy.

Find out more

-

Let’s talk about mental health | Part 1

I sat down with some of our team to talk openly about mental health.

Find out more